Jehovah’s Witnesses: A Cult of Isolation and Fear

A story about the destructive power of false beliefs

Human reproduction is so fascinating to me. We begin our life as a single, solitary cell inside the body of another human being. That cell divides and multiplies over and over and over again, building an organism that will eventually be comprised of 100 trillion cells. Then when it’s time, that tiny entity leaves its host to start its own journey.

On our birthday a beautiful new human joins the world with the seed of an entirely unique story inside of it. In ideal situations, capable parents are there to steward that small person through the complex process of education and growth, and to enrich us with the information and skills necessary to fully express ourselves and live a fulfilling life. These early lessons create a ripple-effect that the life in front of us will be deeply impacted by.

My biological journey began the same way yours did, but the parents who met me when I joined the world believed everything was about to end in global genocide and catastrophic destruction. To them, life wasn’t an exciting opportunity to explore the world, discover who we are, or see what we might create with our lives. Life was a test, and Earth was a battlefield where a war against demonic possessions and a monster called Satan was waging.

They were Jehovah’s Witnesses.

To Jehovah’s Witnesses, the world is a dark and terrifying place. I was taught that we were part of a righteous and persecuted minority who were fighting to survive in a world filled with the wicked slaves of Satan. Those “worldly” people wanted nothing more than to trick Jehovah’s Witnesses into lives of “sin” so that we would die at Armageddon with them. These beliefs were called “The Truth” by everyone around me. We possessed The Truth, and everyone who believed differently was lost, confused, and going to die.

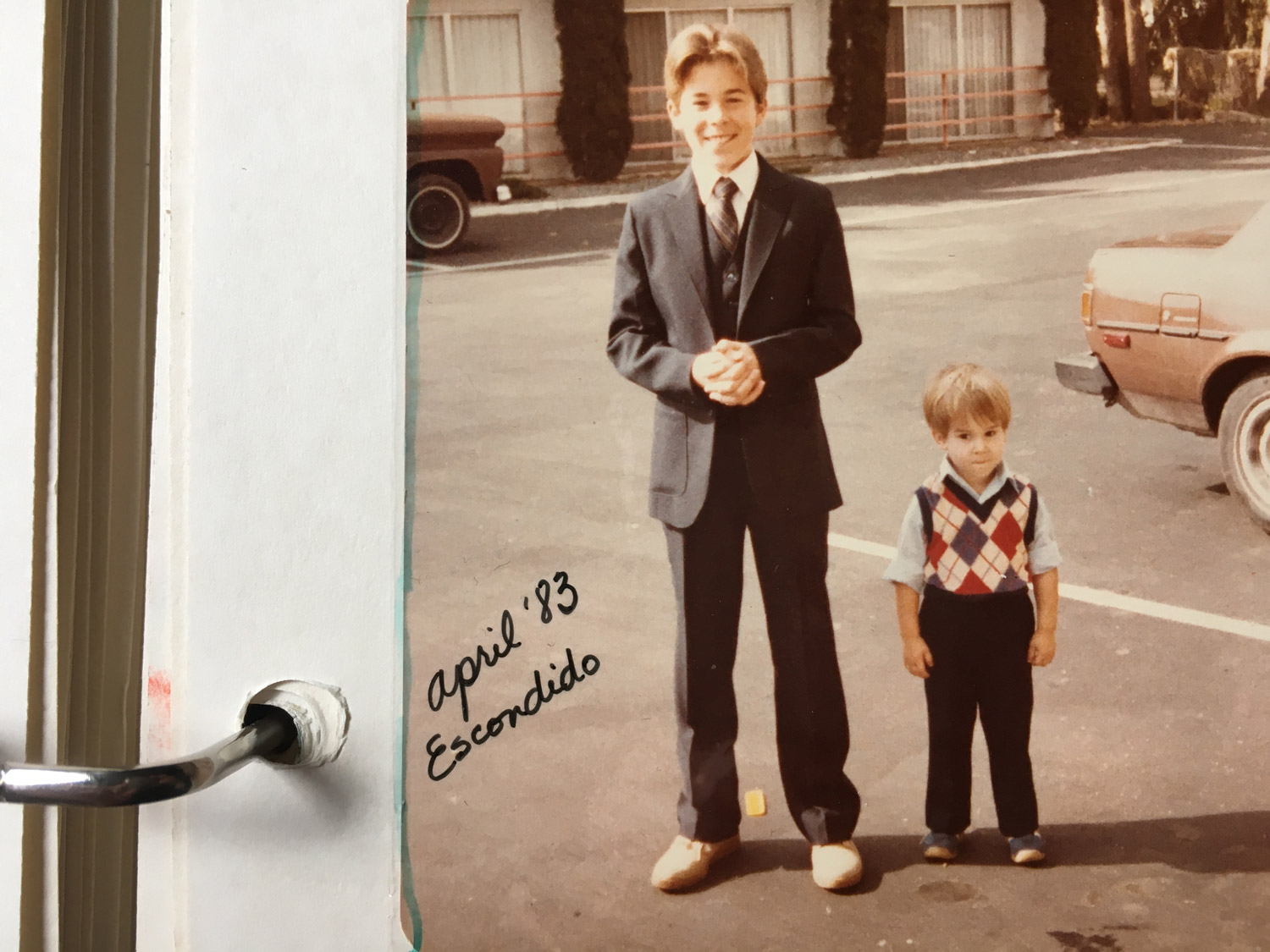

Me (three years old) and my big brother (thirteen years old).

No one could substantiate the things they were teaching me. All they could do was point to the ancient book it all came from as the authority for what the book itself said. We were told to just “have faith” that it was all true. It was seen as a virtue to blindly believe things that other people had written and assured us were real, things that couldn’t be proven. Even when those things didn’t make any sense.

When I was still quite small I started asking questions about why Jehovah was testing all of us and making us live in this terrible world I was being taught to see. If he was omniscient and knew everything (including the future), didn’t he already know who was going to live and die at Armageddon? Why was he making humans suffer like this? The only answers they could offer were things like “god works in mysterious ways,” or “Jehovah loves us so much that he sent his son to die for our sins, and now we have to show Jehovah how much we love him.”

I didn’t understand any of this. Why did I have to be born imperfect because two people sinned in a garden when Jehovah first made the world? Why did every one of their descendants have to be born imperfect and live in pain and die of diseases when we didn’t do anything wrong? They didn’t have answers to those questions, but they were certain I was born with sin already inside of me.

I was about eight years old when I first made this confession to my mother. I remember sitting in the passenger seat of her car as she drove, heavy with shame as I tried to find the courage to confess. I finally found the strength and told her that I didn’t love Jehovah. I didn’t believe in him, and I didn’t understand why we were all being tested. It all seemed so mean to me.

When I was a kid I enjoyed some of the strange bible stories in the books they gave me. I was delighted by the funny story of the man who was swallowed up by a big whale and lived inside of it for three days; the story about the man who put a bunch of animals inside a giant boat he’d built; the story about the woman who turned into a pillar of salt because she had been bad. I also loved stories like The Wizard of Oz, The Never Ending Story, and when Winnie the Pooh visited the land of Heffalumps and Woozles. But I didn’t think that the Wizard of Oz or Winnie the Pooh were real, and I didn’t believe Jehovah was real, either.

I asked her what was wrong with me. I believed I was a bad person because I wasn’t a good Jehovah’s Witness.

I never felt any love or connection when I tried to imagine Jehovah, just fear. I couldn’t see him, but I was told he was always watching me. I heard other Jehovah’s Witnesses around me defend their beliefs when challenged by worldly people, saying things like “well, what if you’re wrong about Jehovah and he really does exist? You’ll die at Armageddon for not believing. The worst that might happen to me is people will laugh at me for believing in him, but at least I won’t die at Armageddon.”

What if I was wrong and that mistake would cost me my life? I didn’t want to die, so I just lived in fear and tried to follow Jehovah’s rules and believe what my parents told me was true.

I remember the sickening grip of terror in my stomach every time the sky darkened abruptly with clouds, or the wind kicked up without warning. The words “it’s happening — this is Armageddon” would ring out in my head. I’d just freeze, and helplessly watch wide-eyed to see how the end was going to start.

To be good servants of Jehovah we were required to attend three weekly gatherings to review the materials the organization behind this cult had written and assigned to us. In 2001, The Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of New York was listed among the top forty revenue-generating corporations in New York City, reporting annual revenue of about USD $951 million. Nothing like that was ever talked about though.

The Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society are the ones who write and print all of the Jehovah’s Witness publications, including The Watch Tower and Awake! magazines. They decide what the Bible means, and tell their followers which of god’s rules have to be followed (rules which change dramatically over time, like whether or not it’s a sin against god for a man to grow a beard). They’re the ones who issue predictions of when the world will end. They decide what their followers are to read and when, keeping them on a steady drip of terrorizing apocalyptic narratives.

I was always discouraged from reading publications that hadn’t been approved by the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society and told that if I did I should disbelieve anything that disagrees with what Jehovah’s Witnesses believe. They said that evolution was a lie, science was a lie, other religions and philosophies were built up from lies, and that practices like meditation opened up your mind to demonic possession.

At these three weekly meetings with our Jehovah’s Witness brothers and sisters, we’d prove to one another that we’d completed the assigned reading. We’d raise our hands hoping that the brother who was leading the meeting would call on us, then we’d read the answers we had carefully underlined in our magazines. The magazines were filled with simple articles about the Jehovah’s Witness’ bastardized version of the Bible and included questions with obvious answers in the text that even children could find. This is how we proved that we were one of the really devoted and good Christians, and identified and judged those that weren’t.

I remember sitting in the back seat as my parents drove us to Dodger Stadium. It was the weekend of a massive assembly where tens of thousands were gathering to worship Jehovah. On either side of the roads leading into the stadium were people with cardboard signs.

Written on their signs were messages telling us that we were being lied to and that what we believed was dangerous. My mom and dad told me not to look at the people or read their signs because they were filled with lies from Satan. Those people were apostates—Ex-Jehovah’s Witnesses who had fallen into Satan’s clutches—and some of the worst people in the world.

As I recall these different experiences, many of them seem so outlandish I question my memory of them. But right on the Jehovah’s Witness website is a page discussing apostates, and they site this scripture:

1 Tim. 4:1: “The inspired utterance says definitely that in later periods of time some will fall away from the faith, paying attention to misleading inspired utterances and teachings of demons.”

Picture of me with my mother at a Dodger Stadium Jehovah’s Witness assembly.

My childhood was very isolated. I shied away from the other Jehovah’s Witness kids because I thought they were weird and cruel, and I wasn’t allowed to associate with other children at school. I was forbidden to participate in any of the holidays or birthdays with my class. I was always the weird kid sitting off to the side during these times, and my mother told me not to eat any of the treats they brought to class because they might be poisoned and have razor blades in them.

My parents divorced when I was seven, and my mom took custody of me. My dad and big brother went to live with grandma Ruth. She was disfellowshipped, which meant the elders in her congregation had revoked her baptism because of some wrongdoing. Being disfellowshipped triggered a series of events where one is expelled from their congregation, disassociated from their friends, and oftentimes estranged from their family.

Grandma Ruth was a mean, ogre-like woman. The ceiling and walls in her home were tinted a gross golden yellow from the cigarette smoke that billowed out of the corner where she always sat. I heard a story once that really summed up the kind of woman she was. To punish her adopted daughter, Grandma Ruth would make Becky stand in the corner on her tippy-toes and place thumbtacks on the floor under her heels. Becky would be left there and when her legs or ankles gave out from exhaustion, well… the thumbtacks were there waiting.

I was afraid of Grandma Ruth and wasn’t supposed to talk to her because she had left Jehovah. I would make a straight line from her front door to my father’s room whenever it was my weekend to visit. I only spoke to her a handful of times before she died.

Both of my parents remarried when I was ten. My mother’s decision to marry Richard — another practicing Jehovah’s Witness — began a new era of abuse and terrorizing beyond anything we could have imagined. My father’s choice to marry Patti brought a cruel and conniving bully into my life and another “sheep” into Jehovah’s “flock.” She seemed to genuinely hate me and wish me harm; I was her little emotional punching bag.

For several years I bounced back and forth between my parents’ homes. As the situation with one escalated to a breaking point, I’d be sent away or would run to the other in hopes of protection. It wasn’t until I was fifteen that I was finally able to stop being a Jehovah’s Witness.

I found myself living with my mother at the time in the hate-filled home she had created with Richard. She had just ended her tenure as a Jehovah’s Witness, but still thought that sending me back into the flock was the answer to the problems she was seeing with my behavior. I refused. I told her that I would never go back to being a Jehovah’s Witness.

After some halfhearted protesting, she never brought it up again. I was free. No longer would I be made to participate in the cult I had been born into. I was far beyond the point of caring what any of the people I’d known my whole life would think of me now, but still, I knew how I’d be seen. I was a traitor. An apostate. I was the worst of the worst, and this was the excuse my father needed to stop speaking to me or feigning interest. I was on the side of evil in all of their eyes now.

But I didn’t feel evil. What felt evil was the way the Jehovah’s Witness called the little girl my father molested a liar when she came forward, saying “Dean is a good Christian. He wouldn’t do that.” What felt evil was the way they coerced my troubled mother into marrying a man who turned out to be a cruel and deranged sociopath. What felt evil was the way they encouraged my friend’s parents to disown him when he told them he was gay, sending him on a path of self-destructive recklessness that eventually resulted in him contracting HIV. What felt evil to me was how they discouraged education, exploration, or developing any sort of security, personal fulfillment, or future. What felt evil was the way that the Jehovah’s Witness spiritual rape and isolating led people I knew to take their own lives because they couldn’t see any other options.

I watched this cult tear family after family apart, and lead their naively trusting followers into profound states of desolation and hopelessness. And I watched a lifetime of isolation and being told that there was no future for me in this world express itself in my own destructive and reckless choices when I finally escaped.

Largely estranged from my father at this point, I only had my mother to rely on. Living with her and her husband meant I was surrounded by their constant screaming, hate, and abuse. I would live there for a few weeks or months before she’d get me in her sights, seething with rage from the life she’d played a starring role in creating, and I’d be thrown out with nowhere to go. This began a period of instability and nomadic homelessness that lasted for several years.

A question answered on the Jehovah’s Witness website sheds a lot of light into the inner workings of the situation I found myself in:

Would faithful Christians welcome apostates into their presence…?

2 John 9, 10: “Everyone that pushes ahead and does not remain in the teaching of the Christ does not have God. . . . If anyone comes to you and does not bring this teaching, never receive him into your homes or say a greeting to him.”

The community I had been raised in wouldn’t help me or take me in because they saw me as their religious enemy. Rejecting me was a righteous act. I stayed for short periods with anyone I could find who would let me stay with them. I felt like a perpetual burden on everyone I knew. I didn’t belong anywhere and never had. Not really.

I was twenty-three before I completely got away from my parents and their insanity. I had carefully disappeared in a way that they couldn’t find me and was living alone in a rural part of Washington. I felt my first breath of freedom from my parents, but everything in me was coated with the sticky resin of their insanity. I spent my first year there hitting the bottom of the nervous breakdown I had started in California and experiencing the full extent of the trauma I had accumulated.

I isolated myself from everyone, tried to get my head above the surface of the pool of darkness I was drowning in, tried to figure out which direction was up, and tried to find reasons to continue living. After a year of hiding and intoxicating myself into senselessness, I moved out of my lonely rural burrow and started laying roots in Seattle. I was surrounded by people and activity again. I was still frightened, wounded, and tortured inside, but I began feeling strong enough to start the all-consuming process of burning down the library of lies I carried in me. If I could destroy what was inside of me I might be able to start over and rebuild myself with things I chose.

I remember sitting at a table in front of Bauhaus Cafe in Seattle and reading a book about science and physics. I was wrestling with the voice in my head as I read every line. It wouldn’t allow anything I was reading to be considered without attack. Everything triggered the deeply instilled distrust I’d been taught about anything that suggested a broader view than what Jehovah’s Witnesses teach.

Evolution was a lie. The estimated age of the universe was a lie. Chemistry was a lie. The Big Bang was a lie. And it wasn’t just science. Spirituality was a lie. Meditation opened your mind to demonic possession. The Buddha was a false prophet. Being still and in the present moment was an invitation for Satan to take up residence inside of me.

This was the period when I first encountered the work of David R. Hawkins and became aware that a method for objectively identifying Truth had been discovered. I realized that the beliefs of Jehovah’s Witnesses could be objectively measured and identified as falsehoods. The narrative I’d been fed about how Jehovah’s Witnesses were the chosen ones and the world hated them because they had “The Truth” began to unravel. I started seeing progress and realized I could change myself and my life if I had courage and worked at it consistently. I started to feel strong and capable. I began to have hope.

The majority of my life has been about my parents’ profound failings to accept responsibility for themselves and grow. In reality, life is not a simple, binary, black-and-white thing that can be summed up as “good” or “evil.” Life is huge, and it’s complex, and it can be confusing when you really open space for witnessing and trying to make sense of it. Life is constantly changing and moving. There are beginnings and endings, which are really just two ways to describe the same events. There are broken hearts and triumphs. There are unknown factors that we do not and can not control. There are mysteries that we do not have the answers to, even though we frequently convince ourselves we’ve solved them because it makes us feel safer.

I spent my time in Seattle rejecting who my parents had turned me into and trying to discover who I might become. Then a window opened for me and I saw the possibility of a life without the constant fear of where my basic needs like housing, food, and companionship were going to come from. A job in California beckoned me, and it was worth diving back into the environment where everything bad in my life had been staged.

I packed up everything I owned into a moving truck, loaded up my beautiful cat who had been my little furry savior many times over, and started down the long expanse of highway that led to Los Angeles. Things felt like they were finally looking up. I imagined this next chapter of my life would be the time when all of my struggles and hard work would pay off. I’d find financial stability. I’d find creative fulfillment. I’d find a woman to fall madly in love with and we’d create a beautiful life together. The clouds had parted, and I could feel the bright warmth of the future I’d dreamed of and worked so hard to achieve beaming down on me.

But within a few days of being back in California, my body began to reveal how much damage had actually been done by everything I’d experienced. The harm hadn’t just been emotional, or psychological, or spiritual — it had impacted everything inside so violently that my nervous system began to shut down and become unresponsive. I’ve spent the past 13 years trying to understand and recover from a neurological disorder no doctor has been able to diagnose, but that is most comparable to Parkinson’s disease.