Chronic Illness and Creating Meaning out of Darkness

A story about the death of who I thought I was and the birth of who I want to be

Having a body is weird. Their strangeness is easy to overlook because they’re so common, but really, we’re all navigating the world in these magical suits of meat that are animated by our attention. These organisms allow us to explore this beautiful planet, they’re how other people and animals recognize us, and they’re central parts of how we define and understand ourselves. Tall, short, man, woman, thin, thick, light, or dark — these bodies can empower us to pursue our dreams, or they can hold us back. Especially when they stop cooperating.

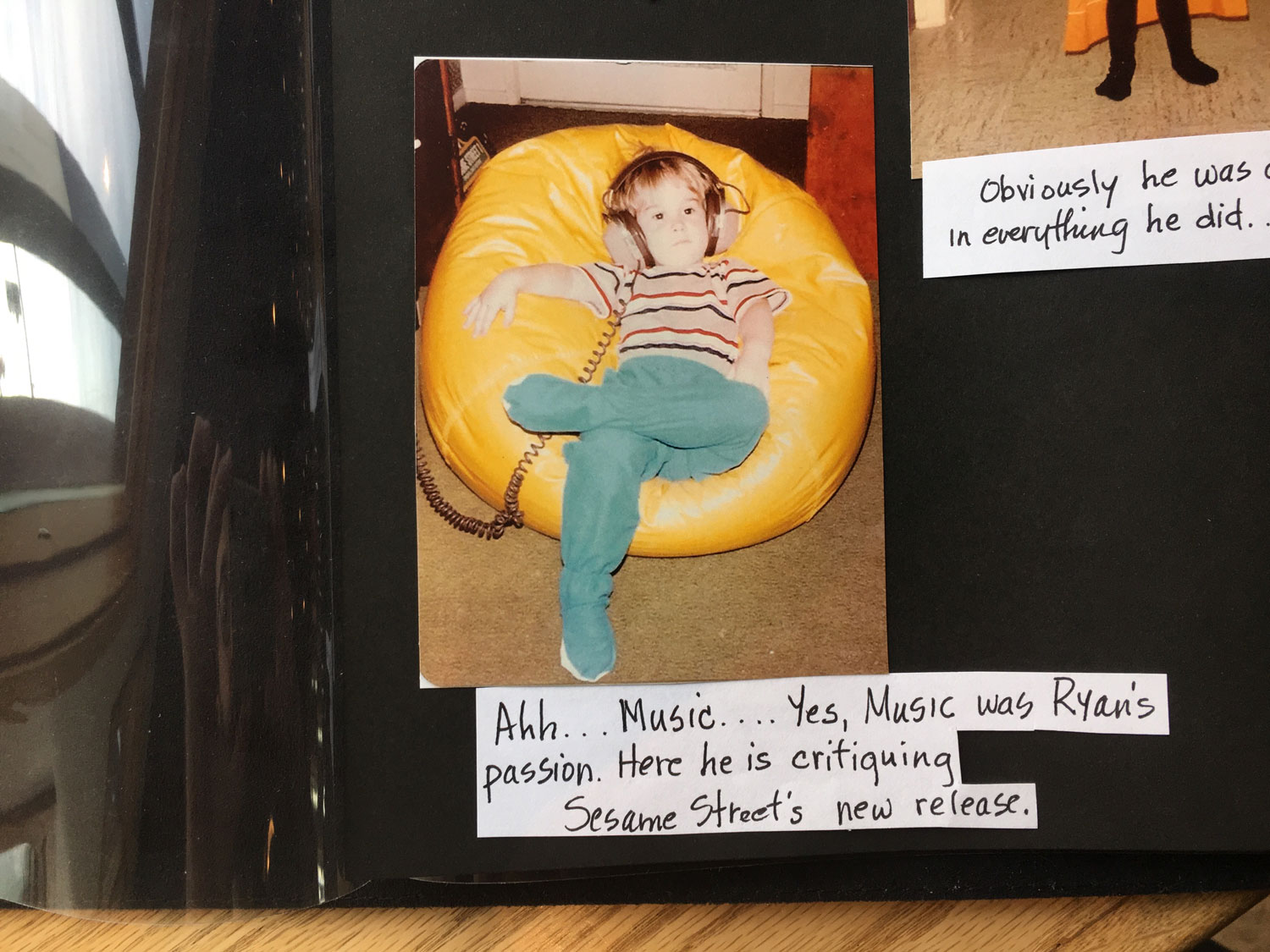

One of my earliest memories is from when I was three years old. I had a very clear sense of why I was here, and that was to be a musician and to fall in love. The vision for life that I saw in front of me seemed like a given — a life so rich and full of magic that everyone would be struck with awe when they saw what I had done. But by the time I was born, an insanity had taken root inside of my parents, and the bounty of poisonous fruits that our family tree had produced became my inheritance.

I was surrounded by a lot of scary stuff back then. I remember my mom crying a lot. I remember my dad throwing his coffee mug at her, missing, and the sliding glass door behind her shattering into a million pieces. I remember my dad angrily throwing something at my big brother, hitting me instead, and my head bleeding. I remember my dad shoving my mom into a corner and punching her repeatedly in the stomach. I remember rumors that she was planning to kill herself. I remember a lot of confusion, fear, anger, and pain. I remember feeling scared and confused.

I don’t remember the specific words I used or think I knew how difficult it would be to keep this promise, but I made a pact with myself back then. I wasn’t going to live my life like these people. I had no idea what the alternative was, but I promised myself that I was going to figure it out. I was going to be different.

Notes my mom put into a photo album she made for me.

This might sound like erudite thinking for a three-year-old, but that’s an accurate account of my felt sense at the time. I didn’t know what words like abuse, mental illness, or hatred meant, but I knew what it felt like to be around them. It felt very wrong. I didn’t want to play that game.

I was on the planet for 23 years before I was able to get away from my family. The first time I ran my fingers across the reigns of my own life was in Washington, and I began the long process of rehabilitating the abused animal that my life had become. The fact that my father is a convicted child molester was back in California. My mother’s mental illness and her sociopath husband were there too. All my memories and experiences of being raised in a cult were back in California as well. But this next chapter in The Story of Ryan started in Washington, and I was determined to start with a clean slate.

I didn’t understand how recovery worked back then. I thought I could move away from California and just leave all that stuff behind, but my parents had done a lot of damage, and that damage lived inside of me. I spent 3-years in Washington completely dismantling my mind and identity so I could start over. It was like taking apart a broken electronic device so I could discard the broken bits and then put it back together again with new parts.

It was grueling, painful work, but I was very successful. Inside of me, the constant horrible beratement and self-torture of memories and fears lessened. I had relinquished so many of the lies I had been taught about how nothing mattered and that there was no future worth planning for. And with the removal of those falsehoods came a desire to take my future seriously. I was tired of the starving artist motif and not knowing where my food and shelter was going to come from. I needed a change, and then a promising opportunity for work presented itself back in Los Angeles.

I do not have warm feelings for California, but returning there felt like a weird certificate of accomplishment. The cocktail of anguish, fear, and hatred that I carried from there to Washington was no longer with me. I felt hopeful, and I believed I had finally turned the corner and broken through the barriers of my past. I was finally about to become the person I’d always felt was inside of me but was never able to embody, and I thought I was closer than ever to my dreams of love and creative success that had always inspired me to stay alive and continue fighting.

But as they frequently do, the things we think or believe about life reveal themselves to be out of sync with reality. Within a few days of being back in California, I noticed that a spot on the left side of my chest had gone numb. It was about the size of a golfball. I very distinctly remember looking down and poking at it in an amused way thinking “That’s weird… what’s that about?” Over the next few days, the patch of numbness got bigger and it started to hurt. I wondered how something could be numb and hurt at the same time. It felt like a numbing vice was crushing my ribcage.

The patch spread from my chest through to my back and then began working its way down into my leg. I observed this thing happening to me but had no idea what it was. Walking started to become difficult. Within a matter of weeks, each step I took required every ounce of my attention so that I didn’t trip over my increasingly unresponsive leg and fall.

Before this, I was an able-bodied twenty-six-year-old. Now, paresis was replacing the effortless control I’d always known, and it was happening very fast. I lay in bed alone one night crying, out of frustration and fear. The toes on my left foot felt as though they’d melted and fused together. I lay there using all of my strength trying to just move them slightly to relieve the discomfort, but there was no movement. Nothing. Wiggling my toes felt like trying to lift a dead elephant above my head, and I had frustrated and exhausted myself to the point of tears.

When you’re emotionally and psychologically unhealthy, you tend to attract other people who are at similar levels of unhealthiness. Part of the process of undoing the damage of my past and growing beyond it had been canceling virtually all of the relationships I had ever formed — especially with my family. So I was pretty alone as I went through this, which made it even scarier. Although, this was during a time that I was talking to my mom again, so I reluctantly told her what was happening.

She blamed her husband’s presence in our lives for what was happening to my body and saw it as confirmation of her belief that we were cursed. She told me that if she was ever able to prove who did this to me she’d kill them. I didn’t say this out loud, but I immediately thought “if this is somehow linked to abuse from anyone, that person is you, mom.”

I didn’t share what was happening with anyone else for a long time after this.

I realized something 10-years later when I published the story about my dad. My parent’s abuse always came packaged with an unspoken threat: ”if you react to what I’m doing to you or tell anyone it’s happening, I’ll make it so much worse for you.” This had the dual effect of making me question whether any of it was even happening, and implanted a deep belief in me that no one cared about me. So I became very skilled at shutting up, hiding, and pushing my reality out of sight. That at least stopped things from getting worse.

While there were a lot of nice people at my new job, I felt that I couldn’t let anyone know what was happening to me. I wouldn’t even know where to start, and I believed that keeping this secret was the only thing stopping them from seeing me as worthless, broken, and then abandoning me. But this spreading illness was mostly invisible, so as far as I’m aware I was successful in hiding what was happening.

No one could see that when I reached into my pocket to get my keys I couldn’t find them. I could hear my keys moving, but I couldn’t feel anything. No one could see that I had gone completely deaf in my right ear, or how much this scared me because it took away 50% of my ability to experience music. They couldn’t see how the world looked as though it were spinning in circles around me and how I was constantly nauseous. They couldn’t see how everything I looked at was doubled or that my eyes were gently shaking uncontrollably and that I was struggling to read.

These sorts of symptoms would go on for weeks, and then some of them would just mysteriously disappear. Then new symptoms would arrive and take away another part of me. But it was my difficulties with walking that posed the greatest threat to my secret. My left leg was numb and felt like it was coated in lead. Every step I took through the office required every ounce of my focus. “Don’t fall down… Don’t fall down… Don’t fall down…” I repeated that silently in my head with every step. I managed this well enough, but then I started losing my ability to speak.

I was talking to a coworker the first time it happened. I suddenly noticed that everything inside of me was locking up and constricting and I couldn’t move the parts that created speech. It was as though I had touched an exposed electrical wire. After several moments everything would relax and I could speak again, but a few minutes later it would all repeat. I had to time the pauses in my speaking to match the rhythm of this constricting paralysis so that it seemed like deliberate breaks in what I was saying.

I spent three years in California trying to identify what was happening to me and reverse it, but my symptoms just kept getting worse. Navigating all of this while also living in a place I so strongly disliked was becoming too much, so I decided to leave. My ability to speak normally had returned by then, but as I left Los Angeles for Portland, Oregon, I could barely walk.

When I arrived in Portland, the movers I had hired filled my new apartment with all of the boxes I brought with me. I dropped something as I was unpacking one night, and as I leaned over to pick it up noticed all of the strength draining out of my body. I slowly collapsed to the floor, unable to stop my descent or pick myself back up. I just lay there with my face on the hardwood, staring at the bottom of boxes thinking, “Uhh… now what do I do?”

For several months, just walking the fifteen feet from my living room to the bathroom felt as though I’d just finished a full day of digging ditches. I’d make it those few feet to the bathroom and then be completely depleted. I’d struggle to make it another few feet to my bed, and then I’d fall into a painful semi-conscious state as my body tried to regain some strength.

My days started at the desk in my living room where I’d strategize how to use my tiny daily ration of energy. Was I going to shower? Could I manage to go grocery shopping? Should I do laundry? Any one of those would be all I could do in a day. And then everything stopped making sense. I started to experience what I had heard about on podcasts where people with brain injuries couldn’t even make a simple decision like choosing a pen with blue or black ink because they lost access to their emotions. Everything became gray and flavorless. I couldn’t understand how I ever cared about anything. I could think about something and remember that I used to love it, but I had absolutely no interest or desire for it.

I watched people and the world around me change and grow. Marriages happened, children were born, adventures were taken—but there was nothing like that for me. I was too sick to participate, but able to watch opportunities and life pass by me. The only emotions I could feel for a long time were fear and a seething resentment for what was happening.

I had dreams. I wanted success in my career. I wanted a family. I wanted a romantic partner. I wanted to adventure through the world with her and be free of what I had inherited from my parents. But instead, I was struggling to just survive. Barely able to walk or see, totally isolated, and still terrified to let anyone know.

My mind felt venomous. I was a shell of who I’d fought so hard to become, and I felt a deep, biting sense of betrayal. The loudest voice in my head was linked to a belief that life had cheated me. But in the background, I could still feel this gentle, quiet, unaffected presence I never fully understood. There was this gentle flickering of an uncompromising refusal to give up or be beaten by anything I was experiencing.

As I was going through photo albums and piecing together memories and sequences of events for the story I wrote about my mom, I came across a picture of me from when I was about three years old. I’m wearing my dad’s socks with a pillowcase tied around my neck like a little superhero. I thought, “I wonder what his superpower was,” and it struck me. His superpower has always been persistence and an ability to find beauty and meaning even in extreme darkness.

I realized that my entire life has been propelled by a desire to create and experience beauty, even if the ingredients others had handed me were senseless and ugly. And I remembered the promise I made to myself when I was still that little kid. The craziness of my parents would not dictate what my life could be. My circumstances would not determine who I could become. And I had never stopped fighting to keep that promise.

I never stopped, but some of my core motivations had always been misguided. I was determined to overcome all of that stuff so that I could become lovable. I was determined to undo all the damage my parents did so that I could be good enough for other people to accept me. I had spent so many years lamenting all that I’d “lost” in the face of this illness because I saw it as taking me farther and farther away from being good enough. It had taken away so much of the currency I thought I needed to purchase lovability.

But I had it all backward. That little kid thought it was his job to buy his mom and dad’s love by taking responsibility for what they were experiencing and to make them look good to their friends. I carried that belief with me into adulthood, but I was no longer just applying that belief to them — I was applying it to everyone, and I was still hiding who I am because I saw myself as so flawed and unacceptable.

It was this “losing everything” that created space for me to begin seeing who I really am. It was this removal of options for superficial distractions that forced me to really look at who I thought I was ”supposed to be.” It was this “losing everything” that created space to hear a voice that had never stopped trying to get my attention.

The quiet, gentle voice in the background was saying “You have a body, but that body is not you. You can do things for others, but what you do is not what makes you valuable. Who you truly are is not determined by what others think about you. Who you truly are is not even determined by what you think about yourself. You are so much more than ephemeral details like youth, status, or approval from others that you’ve been led to believe are the meaning of life. You are so much more than the tiny little cog the world thinks it needs you to be.”

So if the story I’d been fed about what made me me wasn’t true, what was true? Who am I? But there’s the rub — that’s the wrong question. When we ask “who am I?” we’re abdicating our power and looking to something outside of ourselves to tell us a truth that only we can author. The question that life is actually asking us is “who do you choose to be?”

In the context created by the things that have occurred around me, who do I choose to be in relation to it? Do I choose to be the unconscious reactions and tired old stories that I inherited, or do I choose to be something new? And that is the magic of life and of being human: as long as we’re here, we get to keep playing. We get to keep experimenting and trying to figure out the mechanisms of creating ourselves and our world intentionally. We get to learn and grow and create new things.

My life didn’t unfold according to the timeframe or the storyline I thought it should, but what does that mean? Does it mean something went wrong, or just that I misunderstood the question life was asking me? Was life cruel, senseless, and uncaring, or had I simply misunderstood what I was seeing in front of me?

Suckling on my “this is so unfair” story had its payoff, but what was it costing me? Was that payoff something I even wanted? Could I let go of that sad story and try again? Could I start a new story that has a different ending?

How do I want my story to end?

What I’ve observed about life is that what we focus on expands. If my habituated narrative is “people aren’t safe and I’m unacceptable,” I’ll filter out all information that doesn’t support that perspective. I’ll block myself from finding what I actually want because I’m so focused on seeing its opposite.

So what’s the answer? I know that at least a piece of the answer is to show up every day and start again. Not from scratch, but from experience. If I have another day, I have another chance to learn and deepen my mastery of who I’m choosing to be. And that’s pretty fucking special. Not everyone gets that.